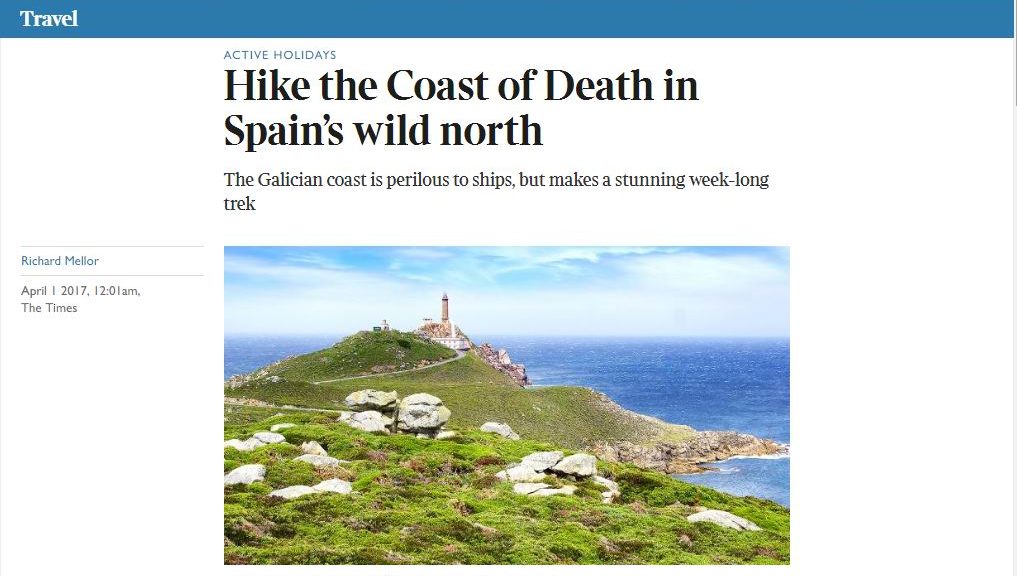

Vilan is looking right at me. Having previously scanned the sea in sweeps, this rust-red lighthouse now has its electronic eye fixed on my slight, slowly approaching figure. I can’t help feeling a bit intimidated: visible from miles afar, Vilan looms large and lonely atop a cape of bleak boulders, the sea angrily fizzing below.

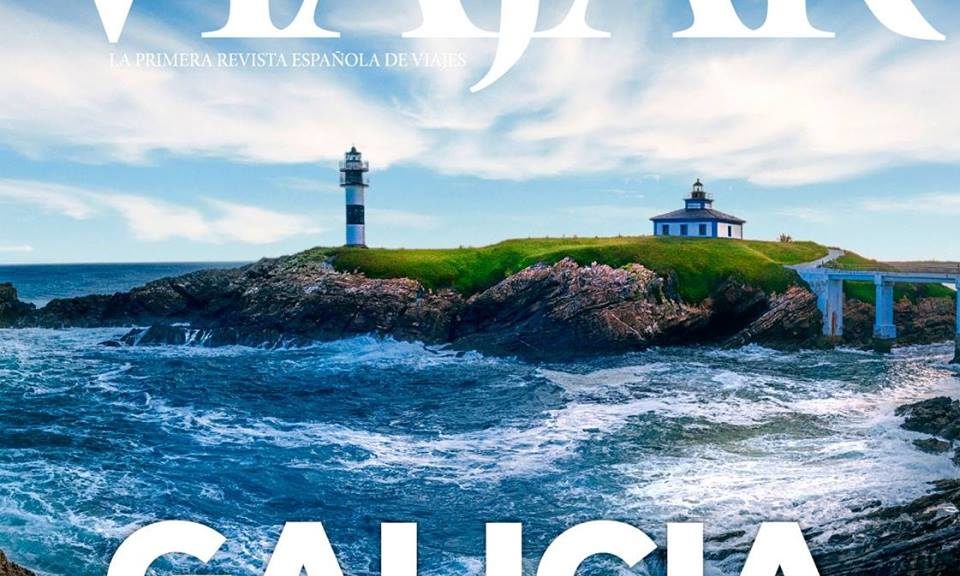

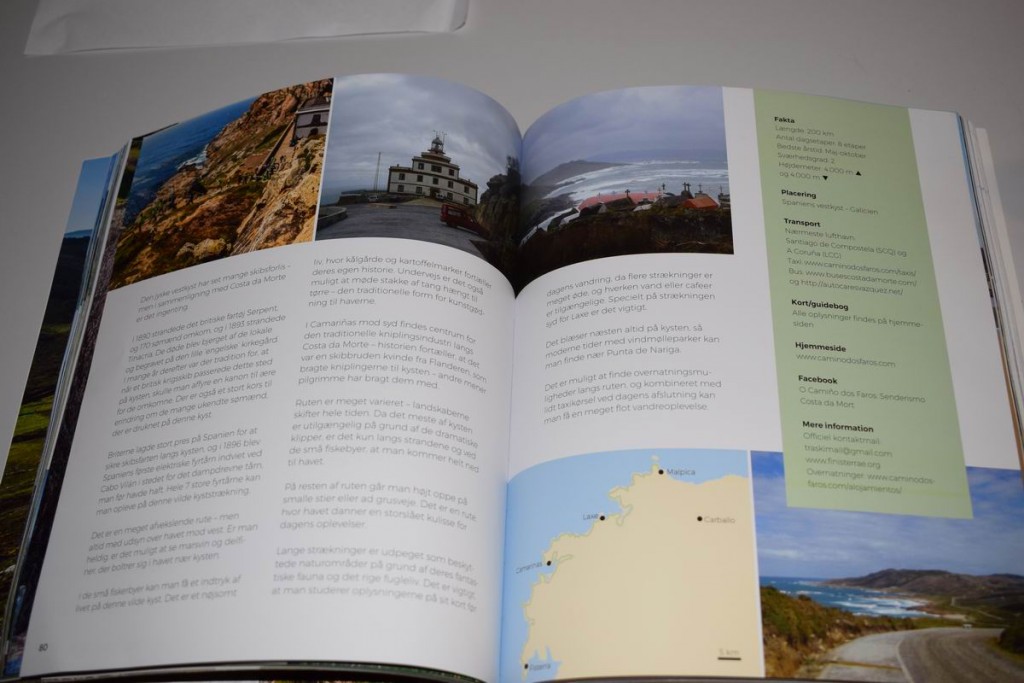

Welcome to the Costa da Morte — or the Coast of Death — in Galicia, the chunk of northwestern Spain above Portugal. As Spanish costas go, this one is worlds apart from Dorada or Blanca — fewer nightclubs and English breakfasts; more barren cliffs, surfers and fish restaurants.

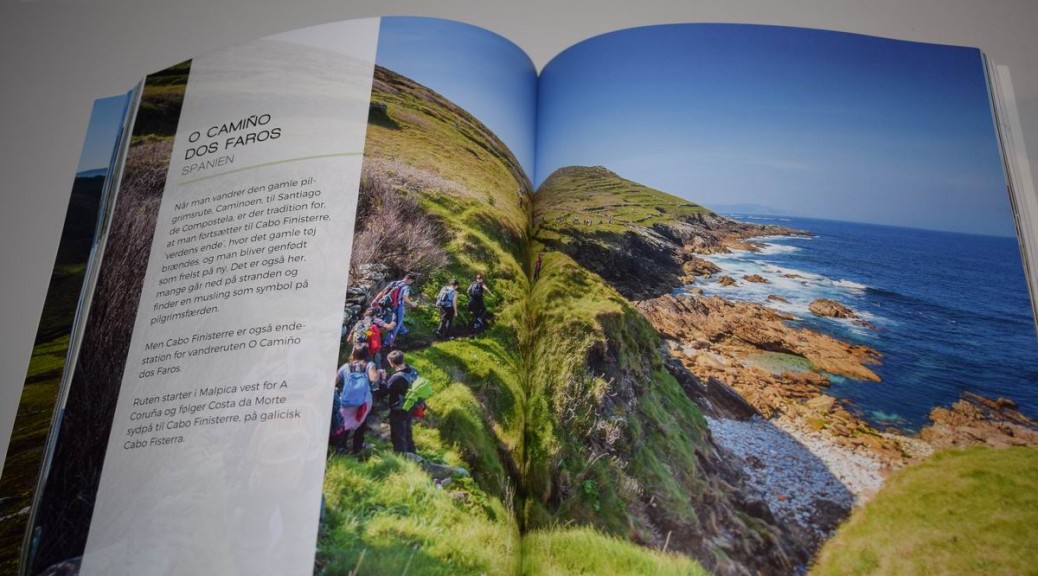

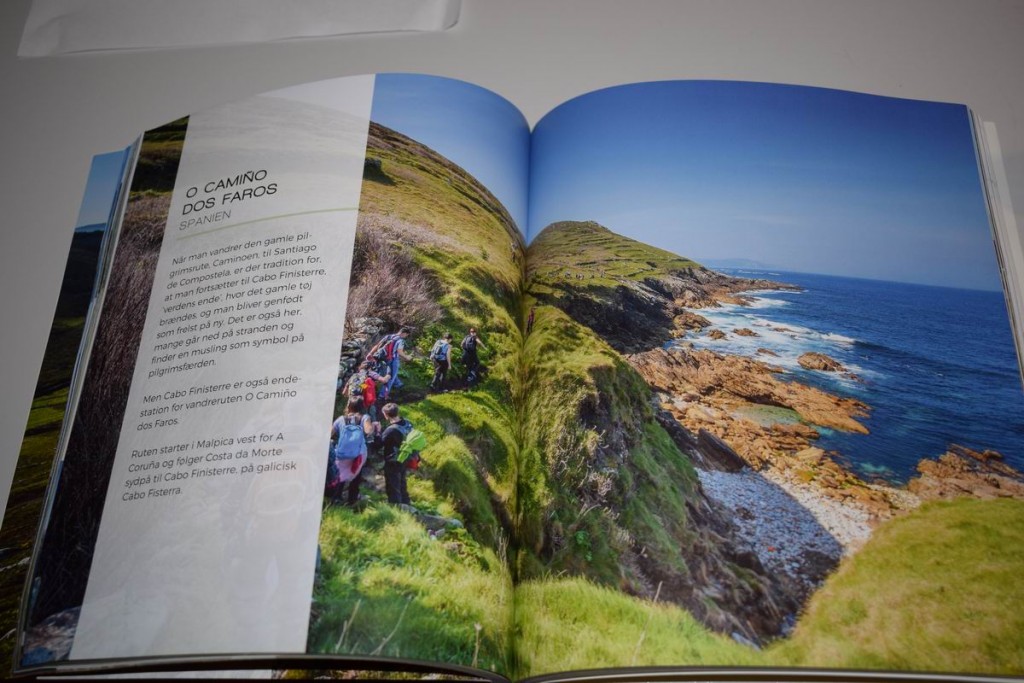

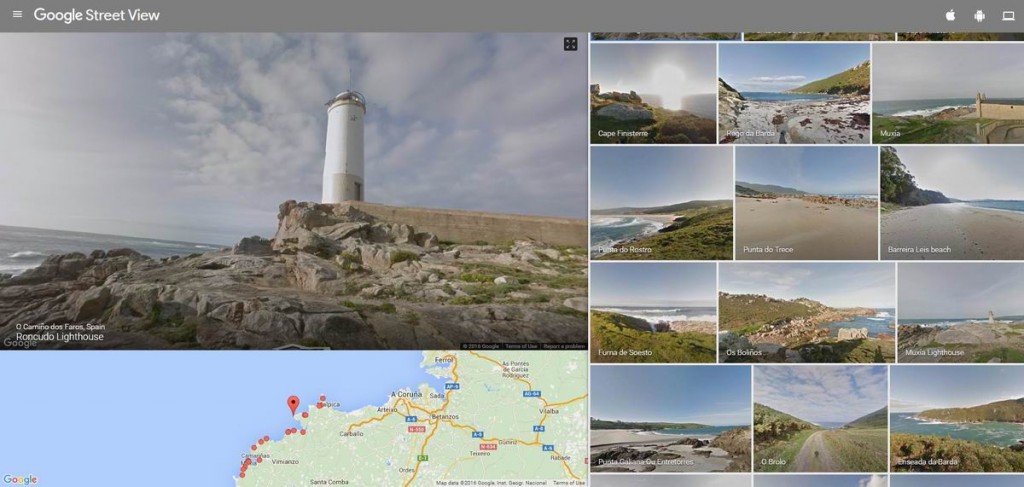

I’m hiking three quarters of it courtesy of a self-guided adventure of the Camiño dos Faros — the “Lighthouse Way”, referencing the several you’ll pass, including the grumpy Vilan. Yet lighthouses turn out to be only one facet of this quirky, variable coastline.

I staggered into Laxe, elated, exhausted and gagging for a cerveza

My first day demonstrated that much. Setting off straight after breakfast, I’d ticked off a paved boardwalk, eucalyptus forest, idyllic riverside and farming villages rich in horreos — old grain houses elevated on stilts to keep rats at bay — all before lunch. I scoffed my sandwiches while inspecting a megalithic tomb, after which a struggle up Monte Castelo de Lourido was rewarded by views towards the town of Laxe, whose long white beach was perfectly framed by a rainbow. “It looks like heaven,” I said to a startled seagull.

I crossed Rebordelo, a pretty cove miles from anywhere, by stepping-stoning my way across gushing channels, tiptoeing around a small waterfall and clambering up some seaweedy boulders; next came pine groves and rhubarb-growing hamlets, then a stony moor festooned with wildflowers. At last I staggered into Laxe, elated, exhausted and gagging for a cerveza. And that was just day one: 16 miles, all manner of landscapes and eight thrilling hours. Phew.

My bones throbbed the next day but at least they were still moving. The Costa da Morte’s name chiefly refers to its dastardly seas, which have claimed scores of boats over the centuries — including some of our own. A small English cemetery houses the 173 victims of HMS Serpent, which ran aground just offshore in 1890.

Those who didn’t are buried around a spartan shrine that is filled with memorabilia: cracked buckets, a bleached pink buoy, some ribbons printed with psalm readings, and, perhaps left in solidarity by mournful modern seamen, an empty rum bottle. Accessible only by foot or bumpy track, the far-flung cemetery must receive few visitors; it felt firmly in keeping with its wild, rather woebegone location.

By the time I finally arrive at Vilan — whose 1896 arrival was too late for those doomed Englishmen — I encounter auks, thousands of them. Vilan turns out to be a protected haven for seabirds.

Coastal days blur happily into each other, a rambling reverie of empty beaches, vast dunes, wetlands, gorse-dodging and desolate rock-scapes

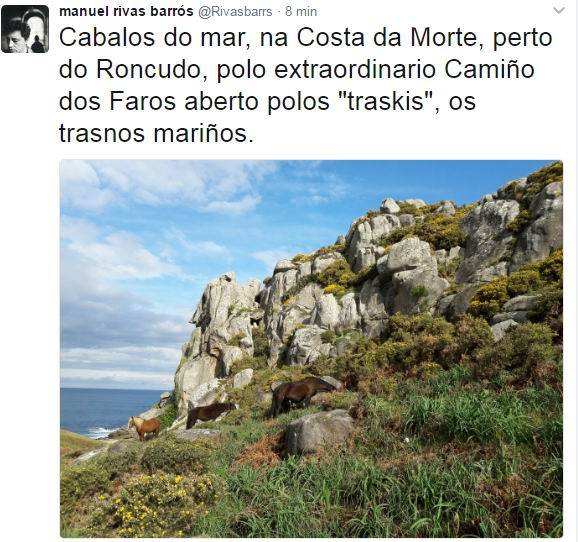

There’s no protection available for the two wetsuited swimmers I spy farther south, thrashing around in an inlet. These are percebeiros, daredevil fishermen who brave frenzied waters to prise goose barnacles — a precious delicacy — from the jagged rocks. Every time my pair disappear amid a tumult of Atlantic froth, I fear the worst, but they survive for as long as I watch.

The next town is Muxia, another sandy resort draped around another Atlantic finger. On its headland is a huge sculpture, A Ferida (“The Wound”), referencing the damage done by a 2002 oil spill, and the Pedra da Barca, an oscillating stone once consulted by sun-worshippers. My own invocation involves glasses of albariño white wine, now established as a post-hike ritual, along with a soak for my weary limbs.

Save for a couple of sorties inland, the coastal days blur happily into each other, a rambling reverie of empty beaches, vast dunes, wetlands, gorse-dodging and desolate rock-scapes that make me feel as if I’m on Mars. I pass no one and see virtually no one. The best parts are the corniches — narrow, plunging wisps of coast path impressively cut into sheer cliffs.

Occasionally I join an extension of the Camino de Santiago, one linking to the seaside. The overlaps are few, however, simply because the more intrepid Camiño dos Faros favours goat tracks over gentle bridleways. If it does join a road, it does so only very temporarily until its light-green waymarks can point down a brambly forest trail, up a rock face or across a squelchy bog.

Those waymarks are fickle. When you’re obviously going the right way, they appear in droves; come to a bemusing fork and — deep breath — they’re nowhere to be seen. So bring a map if possible. Bring hiking poles, too: the craggy terrain is unforgiving on weak knees and rarely flat — there are some lung-busting climbs.

My travel company gives you the option of accompanying your luggage’s daily transfer to the next hotel, and skipping a day, or asking to be dropped at a halfway point. Do the whole thing and you’ll tread 91 bumpy miles over the course of six successive days, hiking about seven hours on each, and that’s assuming no wrong turns.

The last turn of all leads down to Cape Finisterre Lighthouse, a place where Camino de Santiago pilgrims tend to burn their clothes and everyone else stares wistfully out to sea. I retain my apparel, but can’t resist some weary contemplation.

Shipwrecks and rainbows, beach towns and barnacles. The Coast of Death has thrilled me rather than killed me.